1. The Kempner Rice Diet

What the study involved: A strictly enforced diet of almost exclusively carbs

What the study found: Eating an extreme high-carb diet can yield shockingly good results

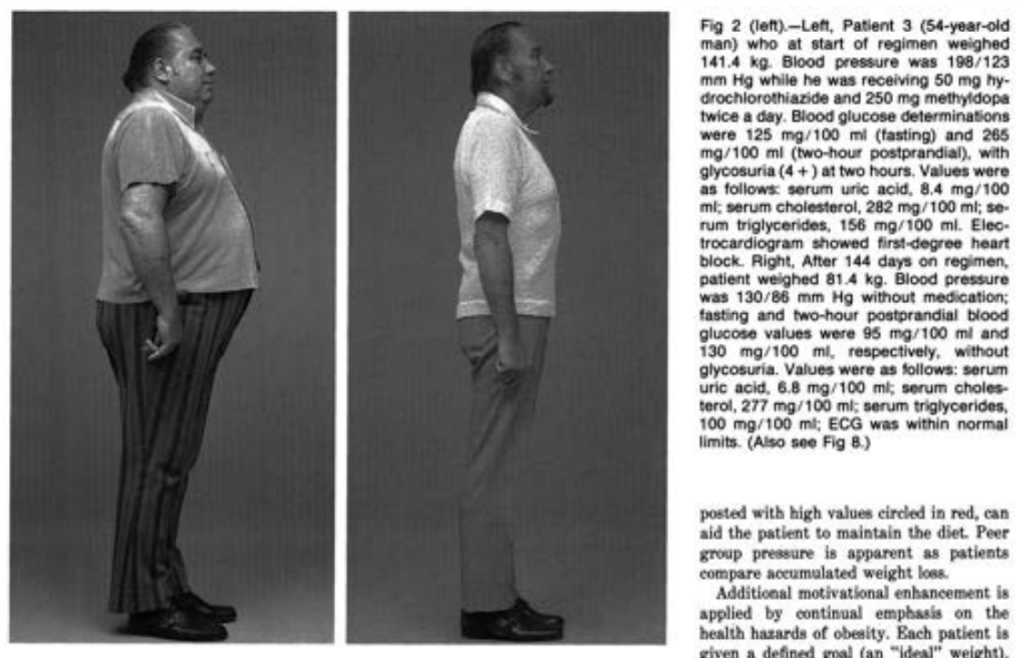

Walter Kempner was a German Jew who escaped Nazism by moving to North Carolina and joining Duke Medical School in the 1930s. He theorized that renal failure could be addressed by lessening the work that kidneys have to do, and came up with the idea of feeding patients almost exclusively rice. Challenged by medical students, he put his ideas into practice.

The diet he designed consisted almost entirely of rice and fruit, with some vitamins added. The diet comprised just 4% to 5% protein and 2% to 3% fat.

In other words, the diet was almost the reverse of the keto diet that became so popular in recent years. Instead of minimizing carbs, it made them about 95% of calories.

It had near-miraculous effects. In one early study, of 192 patients with hypertension because of kidney or vascular disease, 107 saw significant improvements in blood pressure. Notable proportions of the patients saw decreases in heart size, lowered cholesterol, and improved eyesight. Not all benefited and some died, but, at the time, the life expectancy of patients with malignant hypertension was only six months.

Supposedly, a breakthrough came in the 1940s when Kempner instructed one of his patients to eat rice and fruit for two weeks and return for follow-up treatment. The patient, a farmer’s widow, misunderstood because of Kempner’s German accent, and didn’t come back for two months. In that time, not only was her disease gone, but she also lost 60 pounds.

Soon after, people were coming from all over to Durham for weight loss. He bought private homes around Duke and converted them into “rice houses” where his patients could live under close supervision to ensure they stayed on the very strict diet.

Part of the diet’s success appears to have been Kempner’s harsh hands-on style: He browbeat any patient who deviated. He was known as rude but honest.

Many of the patients saw dramatic weight loss. In another, later, study, Kempner put 106 obese patients on the Rice Diet. They came in at an average of nearly 320 lbs, and lost an average of over 140 lbs, most of them in under a year. Most of their health markers improved as well.

His studies were sort of lost to time, in part because they were not controlled trials. Kempner argued that the proper comparison group was the people before they began the diet, and also maintained it would be unethical to deny them treatment, given that people with the conditions he was treating generally faced death in a matter of months.

Still, the success of the high-carb diet should raise questions about the mechanisms by which low-carb diets are sometimes claimed to work miracles.

Sources: https://ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03946#d1e173… https://psychologytoday.com/us/blog/fat-us/201202/my-valentine-the-king-diet-culture… https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1200726/

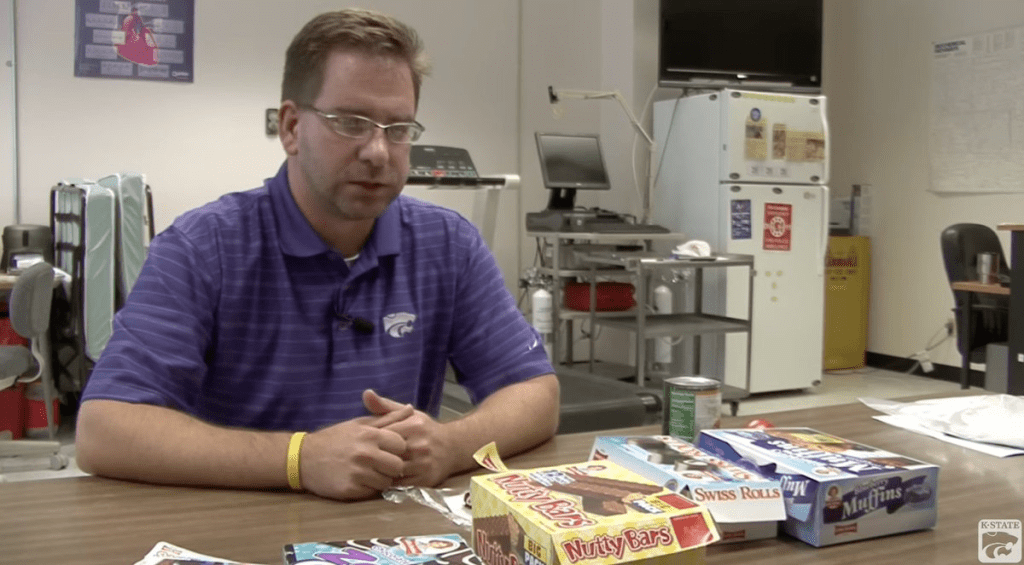

What the study involved: An intentionally terrible diet of junk food

What the study found: It’s calories that matter, rather than specific nutrients

In 2010, Kansas State nutrition professor Mark Haub set out to change the perceptions of how food affects health with a demonstration that it is the caloric content of food, and not other nutritional qualities, that matters for weight gain or loss. He experimented on himself by creating an intentionally terrible diet in which he ate only convenience store snacks, such as Twinkies, Oreos, Doritos, etc., and drank Mountain Dew. He did supplement with protein shakes and ate a can of raw vegetables once a night, but overall the diet was clearly atrocious by most standards. But he limited himself to 1,800 calories a day. He lost weight, fast — 27 lbs in two months, according to one contemporary write-up. His body fat percentage fell from 33.4% to 24.9%. And even though his diet was wildly disproportionately full of sugar and saturated fats, his health markers improved — for instance, his bad cholesterol fell 20%. Apart from the contemporary coverage in the media, I haven’t been able to find much information on this experiment and what happened afterward.

3. The Biggest Loser Study

What the study involved: Tracking the long-term effects of extreme weight loss on the Biggest Loser

What the study found: The body resists weight loss to a surprising and daunting degree, even years later

In a study published in 2016, researchers, most of whom were affiliated with the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, examined what happened to 14 contestants on the Biggest Loser six years after the end of the competition.

The Biggest Loser is a reality show in which contestants engage in extreme diet and exercise to compete to lose the most weight.

The researchers specifically looked at the extent to which contestants saw “metabolic adaptation” — that is, how much their weight loss led to a change in their resting metabolic rate, meaning, the amount of calories burned just living, without any exercise.

The results were surprising — and daunting.

Most of the contestants regained most of the weight they lost and suffered persistent metabolic adaptation even six years later.

The participants weighed 328 lbs, on average, when they began the Biggest Loser. They averaged less than 200 lbs when it was over. Six years later, at the end of the study period, they were back up above 290 lbs, on average. Five of them regained all the weight.

At the end of the 30-week competition, the average metabolic adaptation was 275 calories a day, meaning that their bodies were burning 275 calories fewer than would be expected for a person of their size and body composition. Six years later, after most of them gained weight back, that had grown to 499 calories.

The weight loss sustained over the long term by the Biggest Loser contestants was actually relatively good compared to other interventions, so in a sense the context was a “success.”

But this study shows the extent — and the duration — of the changes that take place within the body to work against weight loss by reducing resting calorie expenditure. Some of the contestants saw a metabolic adaptation of 800 calories a day, six years after the contest.

To put that in perspective, under a set of reasonable assumptions, a 5’10” man who weighed 290 lbs who engaged in only very light exercise would need about 3,000 calories a day to maintain weight. But if that same man was at 290 lbs after competing six years prior in the Biggest Loser, regaining a lot of weight, and suffering a metabolic adaptation of 800 calories a day, he would need to cut to 2,200 calories a day just to avoid weight gain. To lose weight (which he’d surely want to do, given he’s severely obese), he’d have to go even lower.

Perhaps worse, the participants in the study who kept the most weight off also generally experienced the greatest ongoing metabolic adaptation, meaning that their weight maintenance was accomplished by fighting off greater hunger/greater lethargy every day — not because it became easier over time.

4. The fast of Angus Barbieri

What the study involved: A man stopped eating altogether for over a year

What the study found: A total fast need not have any ill effects

Angus Barbieri, a 27 year old obese Scottish man, checked in to hospital one day in 1965 to begin a fast that would last for 382 days.

During that time he ate no food and lost 276 pounds, going from 456 lbs to 180 lbs.

During the medically supervised fast, Barbieri drank tea and coffee and took vitamins given by his doctors, but didn’t eat any food. He simply didn’t eat at all, and lost about three-quarters of a pound each day.

He sustained the fast apparently without any problem. Barbieri maintained his post-fast weight, weighing in at 196 lbs five years later.

His doctors said in a case report that the fast had no ill effects and concluded that “Starvation therapy can be completely successful, as in the present instance.” Note well, though, that Barbieri was watched by doctors the whole time.

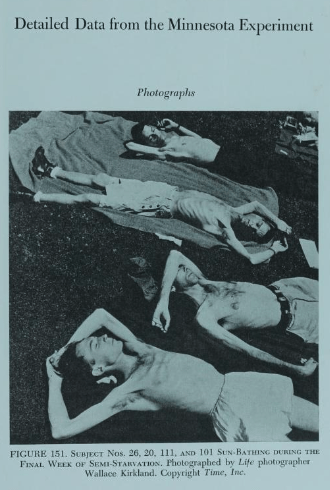

5. The Minnesota Starvation Experiment

What the study involved: A group of men was intentionally starved to see what would happen

What the study found: Going without sufficient food causes profound physiological and psychological changes

During WWII, the prominent physiologist Ancel Keys and other researchers recruited 36 volunteers among conscientious objectors for an experiment on starvation.

They were brought to the University of Minnesota, housed in a lab in the football stadium, and given tasks and exercise — with their diet and energy expenditure kept under rigid control.

Then, their diet was cut to about 1,500 calories a day for 24 weeks, a level thought consistent with famine. Their food was limited to what might be available to Europeans surviving the war: bread, cabbage, rutabagas, turnips, and macaroni.

They dropped the pounds fast: 19% to 28% of their bodyweight. Their resting metabolic rate fell 40%.

Physiological effects: When they began refeeding, the subjects regained more weight than they lost — a phenomenon known as “weight overshoot” that occurs in rehabilitation from starvation.

In general, they seemed to be asking less of their bodies across the board: They had lower body temperatures, reduced sex drives, and decreased heart rates.

Psychological changes: They became preoccupied with food: When they went to the movies, they were most interested in the scenes when the actors were eating.

“I think for the first time, I read Proust because he had something to say about the joys of partaking in food,” Daniel Peacock, then 95 and one of just two or three subjects still alive, told the Pioneer Press in 2014.

One of the men collected over 100 cookery books while participating in the study. Three participants became chefs, and one went into agriculture. Several were kicked out because they sought out unauthorized food.

One participant began having dreams that featured cannibalism only a few weeks into the restriction phase of the experiment.

During refeeding, one of the men amputated three fingers while using an ax and admitted feeling “crazy mixed up at the time.” He said, “I’m not ready to say I did it on purpose, I’m not ready to say I didn’t.”

The study has been used as a guide in developing programs for famine relief, as well as for treating patients suffering from anorexia and bulimia, especially in terms of understanding how they might have difficulty with cognitive or social functioning. More generally, it shows how dieting, taken to an extreme, can totally hijack your life, making it difficult to maintain not just physically but also psychologically.

A 57-year follow-up study found that the experience had no life-long ill effects on the subjects, even though it messed them up in the short term. The psychological and physiological harms they suffered in the short term while they were being starved proved reversible once they were fed.